Elements & issues

The glass skin

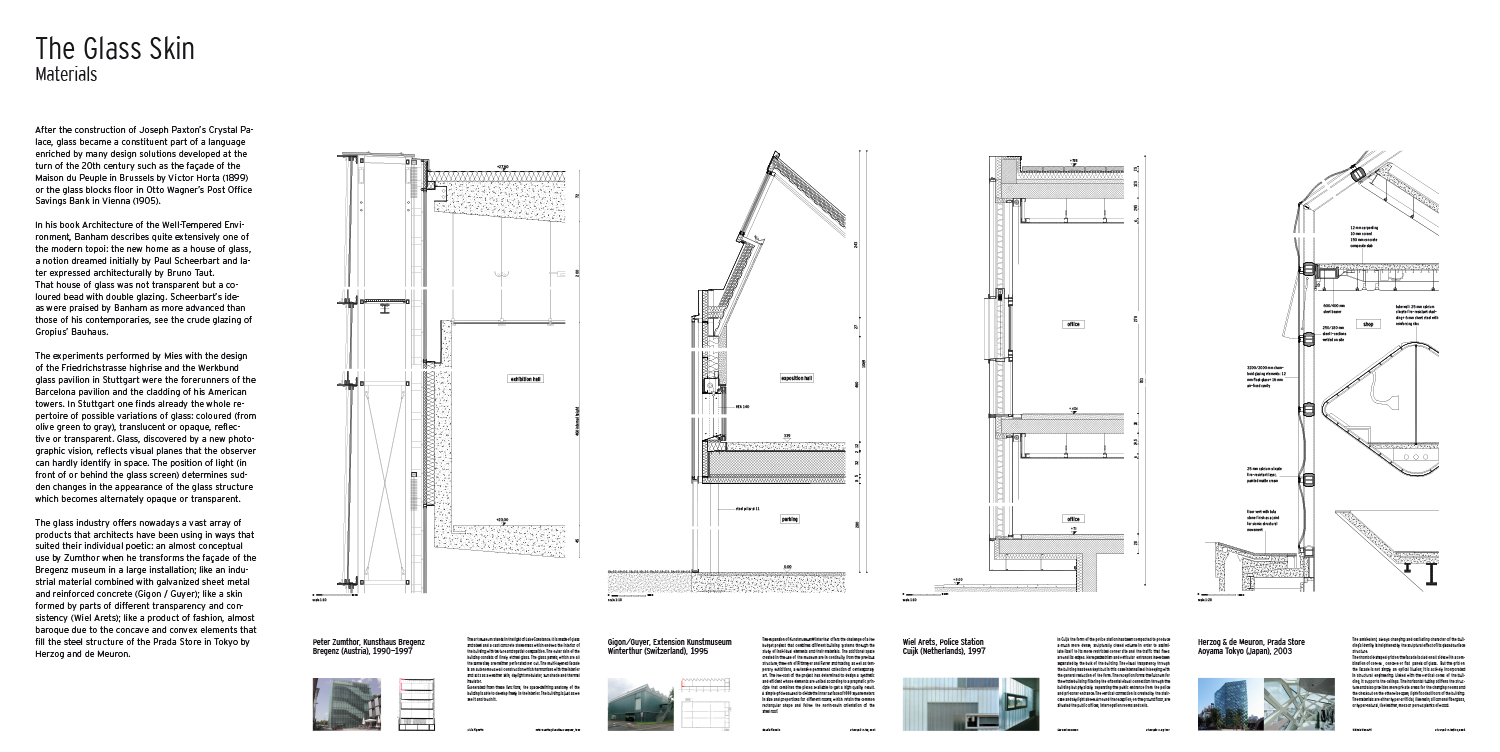

After the construction of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, glass became a constituent part of a language enriched by many design solutions developed at the turn of the 20th century such as the façade of the Maison du Peuple in Brussels by Victor Horta (1899) or the glass blocks floor in Otto Wagner’s Post Office Savings Bank in Vienna (1905). In his book Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment, Banham describes quite extensively one of the modern topoi: the new home as a house of glass, a notion dreamed initially by Paul Scheerbart and later expressed architecturally by Bruno Taut. That house of glass was not transparent but a coloured bead with double glazing. Scheerbart’s ideas were praised by Banham as more advanced than those of his contemporaries, see the crude glazing of Gropius’ Bauhaus. The experiments performed by Mies with the design of the Friedrichstrasse highrise and the Werkbund glass pavilion in Stuttgart were the forerunners of the Barcelona pavilion and the cladding of his American towers. In Stuttgart one finds already the whole repertoire of possible variations of glass: coloured (from olive green to gray), translucent or opaque, reflective or transparent. Glass, discovered by a new photographic vision, reflects visual planes that the observer can hardly identify in space. The position of light (in front of or behind the glass screen) determines sudden changes in the appearance of the glass structure which becomes alternately opaque or transparent. The glass industry offers nowadays a vast array of products that architects have been using in ways that suited their individual poetic: an almost conceptual use by Zumthor when he transforms the façade of the Bregenz museum in a large installation; like an industrial material combined with galvanized sheet metal and reinforced concrete (Gigon / Guyer); like a skin formed by parts of different transparency and consistency (Wiel Arets); like a product of fashion, almost baroque due to the concave and convex elements that fill the steel structure of the Prada Store in Tokyo by Herzog and de Meuron.

Read text

Peter Zumthor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Bregenz (Austria), 1990-1997

The art museum stands in the light of Lake Constance. It is made of glass and steel and a cast concrete stone mass which endows the interior of the building with texture and spatial composition. The outer skin of the building consists of finely etched glass. The glass panels, which are all the same size, are neither perforated nor cut. The multi-layered facade is an autonomous wall construction which harmonises with the interior and acts as a weather skin, daylight modulator, sun shade and thermal insulator.

Exonerated from these functions, the space-defining anatomy of the building is able to develop freely in the interior. The building is just as we see it and touch it.

Giulia Vignotto – Peter Zumthor, Kunsthaus Bregenz, 1999

Gigon/Guyer, Extension Kunstmuseum, Winterthur (Switzerland), 1995

The expansion of Kunstmuseum Winterthur offers the challenge of a low budget project that combines different building systems through the study of individual elements and their materials. The additional space created in the use of the museum are in continuity from the previous structure, the work of Rittmeyer and Furrer and hosting, as well as temporary exhibitions, a extensive permanent collection of contemporary art. The low-cost of the project has determined to design a synthetic and efficient whose elements are united according to a pragmatic principle that combines the pieces available to get a high quality result.

A simple grid was used to divide the inner surface of 1000 square meters in size and proportions for different rooms, which retain the common rectangular shape and follow the north-south orientation of the shed roof.

Claudio Vianello – El Croquis n. 102, 2001

Wiel Arets, Police Station, Cuijk (Netherlands), 1997

In Cuijk the form of the police station has been compacted to produce a much more dense, sculpturally closed volume in order to assimilate itself to its more restricted corner site and the traffic that flows around its edges. Here pedestrian and vehicular entrances have been separated by the bulk of the building. The visual trasparency through the building has been kept but in this case internalised in keeping with the general reduction of the form. The reception forms the fulcrum for the whole building filtering the orizontal visual connection through the building but physically separating the public entrance from the police and prisoner entrance. The vertical connection is created by the staircase and skylight above. Arround the reception, on the ground floor, are situated the public offices, interrogation rooms and cells.

Giovanni Donazzan – El Croquis n. 85, 1997

Herzog & de Meuron, Prada Store, Aoyama Tokyo (Japan), 2003

The ambivalent, always changing and oscillating character of the building’s identity is heightened by the sculptural effect of its glazed surface structure. The rhomboid-shaped grid on the facade is clad on all sides with a combination of convex, concave or flat panels of glass. But the grid on the facade is not simply an optical illusion; it is actively incorporated in structural engineering. Linked with the vertical cores of the building, it supports the ceilings. The horizontal tubing stiffens the structure and also provides more private areas for the changing rooms and the checkout on the otherwise open, light-flooded floors of the building. The materials are either hyper-artificial, like resin, silicon and fiberglass, or hyper natural, like leather, moss or porous planks of wood.

Michela Mansutti – El Croquis n. 129/130, 2006